Yoav Sorek | The Decline of the Majestic Man

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready... |

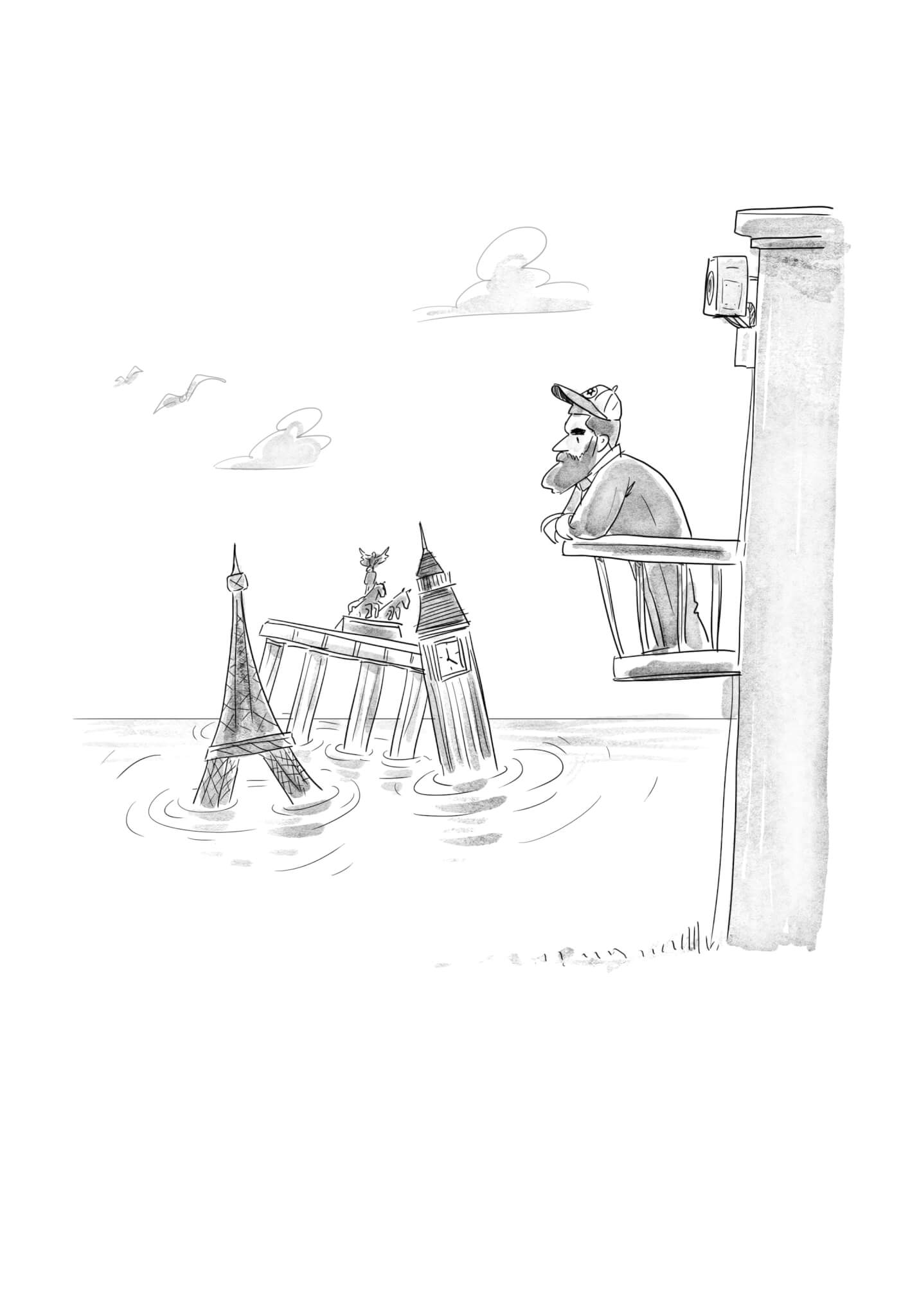

The continent that produced modern culture when we were still an inseparable part of it is becoming a new Atlantis, and it is too soon to tell what the crashing waves will bring. Another rapt and anxious view of Europe from Jerusalem.

"Majestic man." This is what Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, in his famous essay “The Lonely Man of Faith,” called the man whose creation is described in the first chapter of Genesis. He was the man created "in God's image," male and female, to rule over the fish of the sea and the birds of the sky, and also the one that the Creator entrusted with all of creation. He was the one God blessed to be fruitful and multiply and fill the land just a moment before He handed him the keys to the kingdom and withdrew for His Sabbath rest.

Majestic Man was invested with supremacy and responsibility, the ethics of a serving elite: It is man’s right and duty to enlist the entire world in the great projects he undertakes, and it is his moral judgment that will be the ultimate arbiter of right and wrong, to punish the wicked and reward the righteous. "He who sheds man's blood — by man shall his blood be shed," – this unbearably grave responsibility was imposed on the sons of Noah because, "He made Man in God's image." However "colonialist" and "hegemonic," "anthropocentric" and "Eurocentric" this approach may be deemed today, it is what created the enlightened world we live in, and that produced the most successful civilization in the history of the world.

For many years, Majestic Man lay dormant, a theoretical concept. While Psalm 8 may have sung man's praises –

“What is man that you are mindful of him, and the human creature, that You pay him heed? You have made him a little lower than the angels and crowned him with glory and honor. You have given him dominion over the works of Your hands; You have set all things under his feet: All sheep and oxen, and the beasts of the field, the birds of the heavens, and the fish of the seas, all that swim on the paths of the seas,”

in reality, man never exercised that degree of control. Even today, human beings cannot command the migration of birds or the fish of the seas, but in the ancient world, man was entirely at the mercy of the forces of nature.

Yet suddenly, thanks to the revolution of history in the Modern Age, the true Majestic Man was finally able to take the stage, cutting through many long centuries of almost static history. The New Man was finally able to assume the responsibility that God had invested him with and he began to change, shape and cultivate the world as he studied its internal logic and conquered the forces of nature with dizzying alacrity. The swift development of science was accompanied by a new approach to power and the role of humanity: Man was now driving the chariot of progress that would bring civilization to uncharted provinces. Man would now control not only animals and the forces of nature, but also cultures and civilizations that had not yet seen the light: And so Daniel Defoe's Robinson Crusoe weans Friday of his cannibalism; Jules Verne's British gentleman Phileas Fogg saves a young Indian woman from the barbaric customs of India and then also his companion Passepartout from those thought to be Indians — the North American ones; and David Livingston, the Scottish missionary and explorer – both an advocate of colonialism and an uncompromising crusader against slavery in any form – brings the true faith to places “where no white man had been before.”

All this happened in Europe. But lest there be any confusion, this is not geographical Europe, Europe of the maps that stretch all the way to Asia, and nor is it the Europe of the "Holocaust of European Jews." We are referring to the Europe where modern Western civilization was born — the part located north and west of the Alps, including the Alps – Britain, Germany, France and the Low Countries. Indeed, the advanced and glorious civilization that evolved in these lands aroused the envy of their neighbors, in the south on the shores of the Mediterranean and east in the steppes of Russia, who tried — and sometimes succeeded — to stretch the "European" blanket to cover them, or alternately to mimic and copy it.

St. Petersburg’s Western European ambiance was the result of the Russian Czars’ proactive initiative to import Western airs to their backward country, and Budapest of the turn of the twentieth century was a successful imitation of Paris. But the disparity remained, as proved by the current economic crises in the countries of southern Europe and the desire of the more "European" regions of northern Italy and northern Spain to dissolve their forced marriage to their Mediterranean cousins. The scarfed babushkas stacking hay in the villages of Romania or the men who fill the tavernas on the isles of Greece every evening are not the "Europe" of Western civilization, of the great leap forward to a humanistic and technological culture, but are rather the unmediated vestiges of the traditional, laid-back cultures that are in no rush to get anywhere. Although it too is Europe in the geographical and economic sense, it is not the Europe that is the subject of this essay, this lament.

*

Majestic Man links two discrete ideals: The ideal of civilization: to transform the savage into a member of civilization, to conquer and regulate nature, create a network of roads, bridges and drainage systems; and the ideal of progress, that of change, revolution and rebellion, in short: the rethinking of ideas and the belief that things can be done better, both for society and in terms of settling the land. Some might consider this the merging of the ideal of the Romans – the men of the majestic past, builders of aqueducts and pavers of all the roads leading to Rome – with the ideal of the Jews – the people who left Egypt and became the standard bearers of faith, messianism and utopia, the nomads who above all needed resourcefulness to survive.

For a long time, this combination of Rome and Jerusalem did not bear fruit. It produced Christianity, the Middle Ages, but also, to a great extent, conservatism and stagnation. Rabbi Tzvi Yehuda Kook, like Nietzsche before him, but of course from different sources, taught that Christianity is defective: Instead of an empowering encounter between paganism and faith, what was born was a distortion that demeans man's stature. Still, ultimately, it was the Christian world that produced the great breakthroughs of the West, those that produced the New Man, the Majestic Man who creates new worlds in geometric progression, and the culture that conquered the world, in practice and in theory — and continues to shape it even after it has once again converged back to its relatively small countries of origin, mumbling words of apology and sinking into demographic desistance.

Anyone crossing the Alps with eyes wide open clearly feels the tremendous civilizational force of human culture that evolved there. Man lives in the shadow of mountains, forests and water currents, overwhelmed by the mighty forces of nature embodied in them. At first glance, one might think he is merely adapting himself to them. But a second glance will often reveal that pastures and hamlets hide sewage systems beneath that prevent them from becoming swamps, that the forests are all managed, mapped, surveyed and supervised, that the huts built high up in the mountains to shelter the summer herdsmen are designed to capture heat for those who need them and to last for many years. We in Israel were raised on the ethos of draining the swamps, but life in the Alpine districts apparently required a far more significant settlement effort, even before the enormous dams that collect water and generate electricity and the highways that crisscross valleys and pierce mountains. But all this would have remained no more than the enduring routine of summer pastures and winter hibernation, with the ding-dong of cowbells and tolling of church bells, in a society that had already acquired the life skills required in these places, handing them down from one generation to the next. This is the labor-intensive culture of civilization, but it blazes no trails. It alone could not have produced the New Man, the one that evolved in the restless cities.

And indeed, from a bird's-eye historical view, for the Roman-Jewish match of a settling power and a path-breaking force to bear fruit, it would be apparently necessary to displace time and place. The displacement in time is well known: Modern Man emerged only after a series of historical processes (the most obvious among them being the Reformation, the printing press, the discovery of America and demographic changes), without which we would still be denizens of the Old World. But there was also a geographic displacement: The New Man did not emerge from sun-drenched, heritage-rich Rome, Jerusalem, Athens or Byzantium, but rather north and west of there, in the cheerless, grey cities of trade and industry on the shores of the Atlantic. Perhaps it was the climate, perhaps the Germanic mentality of the various Teutonic tribes — but that fact cannot be denied.

Among the Jews too, the Ashkenazi tradition, eventually the dominant force among the Jews of the modern age, was born of Jews who departed from the shores of the Mediterranean and the Eretz Israel traditions of southern Italy to settle in the Rhineland. In wake of expulsions and opportunity, the Ashkenazi tradition was not limited only to Ashkenaz. Moving eastward to the savage provinces of Poland-Lithuania, the Jews of Ashkenaz brought with them the heritage of a more developed human world, stretching the European blanket just a bit further. In recent generations, our Sephardi brothers also became an integral part of the process: As quintessential agents of modernization, the traders of Baghdad and the Jews of the Maghreb became natural allies of the colonial forces, bringing a certain degree of modern Western Europe’s tempestuous spirit to the sleepy cities of Asia and Africa swathed in their eastern fabrics.

We owe a great debt to this Europe, whose misfortune we are oft inclined to celebrate. The unspeakable horror of the Holocaust, the unprecedented depravity of the Nazis and their allies makes us forget — quite rightly, but also somewhat mistakenly — the glorious civilization that evolved there. The Teutonic heart of Europe embodies not only the darkest depths of horror, but also its antithesis: Majestic Man finally claiming the mantle of responsibility bestowed upon him by God in Genesis, as he freed himself from subjugation to nature and repudiated Adam's curse, the curse that caused so many generations to deplete their days in desperate pursuit of their daily bread, leaving only a tiny elite able to live a life of human dignity. Indeed, it is easier to cling longingly to the relatively philosemitic Anglo-American civilization, but let us not forget that Anglo-Saxonism is half Saxon and that Protestantism emanates from the Lutheran Reformation. In other words, there is no English without German – not only the language of the murderers but also the language of our very own ancestors, the mother of Yiddish in which we feel so at home.

This Europe is waning. Oswald Spengler already predicted the decline of the West in the early twentieth century, but based on a different scenario and in different circumstances. Paradoxically, after the European model has been copied all over the world, we now sense a different decline, one whose direct cause is the demographic downtrend, but whose roots run far deeper. They lie in cultural decadence and existential despair, whose inception may lie in Europe’s withdrawal from the colonial project combined with relativistic multiculturalism. A developed and mature culture needs a sense of mission, a goal, something an inchoate culture can manage easily without. And from the moment Europe gave up that pretension, it began to erode. Absent a historic watershed, this decline will continue, leading Europe into a different reality.

Indeed, Europe has always absorbed migrants, and cultures tend to shift and mutate every so often, but geography isn't everything. Culture is handed down from one generation to the next; it is etched in the genes, in ethos and lifestyle. Migrants can adopt it — if they come from a weak culture and seek to assimilate into a stronger one. But when the host culture is in a state of decline, in a state of submission, as Michel Houellebecq puts it, it is unable to assimilate the newcomers into itself. And if the newcomers are not homeless refugees, but rather representatives of a very different, adversarial culture – the chances that European Western culture will survive are slim.

In the modern age, wrote Ioram Melcer in a previous excellent essay, in Eretz Acheret (November 2001), the Jews were the lifeblood of Europe. They turned the small cultures into elements of a greater fabric, one of progress and humanism. Europe rid itself of its Jews in a cruel act of self-destruction, and now, a lifetime later, Europe is shrinking into oblivion. While there may be poetic justice in this, it is unquestionably a tragedy.

Perhaps, in the spirit of our Jewish legends, this is the decline of the "fourth animal" of the Book of Daniel, the Kingdom of Rome, and it is something we must observe from without, seeing in it preparation for the ascent of a better alternative. We can also, in the spirit of the centennial since the Balfour Declaration, distinguish the Anglo-American element from its continental sources, and view the process as the West repudiating its anti-Semitic half. The history being written today appears to be a figurative realization of the process: It is not the Iberian Peninsula that is breaking off from the continent, as in Saramago’s fantasy, mentioned by the previous writer, but rather the British Isles, with the breakup nicely dubbed Brexit.

We can also — based on a universal messianic Return-to-Zion approach — view Zion as the alternative, to view the Jews who brought here the fruits of the different civilizations as the "gatherers of the sparks," who will together help us build, here on the shores of the Mediterranean, the great Tikkun. There is plenty of evidence for this too in view of the veritable marvels occurring here in the land of our forefathers, the only free Western country not threatened by demographic decline, and whose optimism metrics are constantly on the rise.

But when Miriam, the protagonist’s Jewish lover in Houellebecq's Submission, decides to leave the now-changed Paris and move to Israel, Francois kisses her and sadly remarks, speaking for all Frenchmen: "We have no Israel." This is the tragedy in a single sentence. Not everyone has a Zion, and for very many, the decline is a downward tailspin.

As those who draw on European civilization and who made crucial contributions to its formation, we cannot contemplate the events occurring in Europe with indifference: Anxious and riveted by the upheavals of history as we ponder the implications of it all, we will continue to closely observe the continent. Right now, it appears to be on its way to becoming Atlantis, but who knows? Perhaps, like the Phoenix, it will rise anew.

Translated to English by Ruchie Avital

The town of Český Krumlov in the Czech Republic. Photo: Bigstock