For Future Generations: A Basic Law to Limit the Debt

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready... |

Deficit budgetary spending necessarily leads to financial irresponsibility, including among the best of our elected representatives. It is our moral duty to restrain the national debt, and this can be done via legislative mechanisms.

“Turn that minus into a plus with a loan from Isracard.” So ran the campaign of a credit card company launched at the end of 2018. Fierce public and media criticism of the campaign erupted immediately, ending with a demand of the bank supervisor than Isracard end it at once. Why were the critics so incensed? Loans are not a new thing, and indeed are not even a negative thing; to the contrary: Loans are one of the most basic engines of growth. The rage erupted because Isracard was encouraging Israeli households to take out loans, not for the purpose of investing or economic opportunity, but to ostensibly cover ongoing deficit behavior in which spending outpaced income. Everyone could see that taking out a loan to cover overdraft does not solve the problem – it worsens it. After all, we are effectively talking about taking a new loan to cover an existing one – the debt does not disappear, it is simply put off to a later date to come back bigger, with interest. As a consistent behavior, this is a recipe for disaster, bankruptcy, and complete economic fallout.

Many readers have no doubt been exposed from time to time to calls for urgent economic help for miserable orphans whose father abandoned them or suddenly died, leaving them mired in debt and facing repossession orders and liens. Alongside the feeling of mercy and frustration in light of the state of the innocent children, a sense of negative sentiment arises towards that father, whose irresponsible behavior condemned his children to economic distress. All the more so is this the case when we are dealing with indebtedness born not of distress, but a man who secretly lived a double life: Dealing in gambling or living high on the hog without sufficient economic capacity and hiding it from his family, only in an inevitable moment of collapse to hit his family with the consequences like lightning from a clear sky. This is a moral nadir worthy of contempt. A reasonable person responsible for himself and concerned for the future of his family does not act like this. If so, how can we agree to a state behaving in this way?

The State of Israel, like most western states, maintains a deficit fiscal policy: It spends more than it takes in, covering the gap with loans taken out from various bodies. Very much like a household or business, the very taking out of a loan is not necessarily a negative thing. A loan can be a driver of growth if it serves to make a good investment which provides the lender sufficient resources to return the loan and interest and still be left with change. It can even be a necessity, in times of crisis where there is an emergency need for cash flow, after which one can recover, tighten the belt if needed, and return the loan. But a policy of irresponsible loan taking for unproductive purposes and not in time of emergency leads to a debt which grows to the point of being a true threat, and by the time the disaster comes – it’s too late to fix it. Still, such conduct characterizes most countries in the western world to one extent or another – including Israel, whose history of national deficits and debt has already almost brought about a complete disaster in the past. How is this possible?

In this article, we will seek to present to the reader the reality which enables this dangerous economic behavior and its norms, explain the problem of the debt and deficit-based conduct of the State of Israel, show that the national debt policy is based on mistaken ideas and is even morally deficient, and primarily to warn against the reasons which lead a democratic state to adopt a debt-based policy which necessarily leads to its exploitation for improper purposes, which leads to irresponsible economic behavior. We believe that there is a need for a constitutional mechanism that limits the government’s ability to take on debts, to ensure that our children don’t end up being like those orphans facing dire straits due to the irresponsible conduct of the public representatives elected by their parents. Towards this end, we will propose a draft proposal for a new Basic Law: The Deficit, which will protect the State of Israel from this danger we now face.

How Debt is Born

Every government has three ways to fund its public expenses. The first is to increase income by raising taxes. In today’s Israel, like other western countries, tax revenue does not cover public expenditure. Government spending, very much deliberately, always outstrips revenue. This gap is known as a “deficit.” The funding of the deficit can be done in two ways: Printing money and taking out a loan. The loans of each year accumulate into a national debt, which is the total of the money owed by the government. The government takes out loans via the issuance of bonds acquired by private investors, institutions, and even foreign governments, and which the government pays off with interest. Most of the debt, some 87%, is raised within Israel, and the rest abroad.

Israel’s debt is constantly growing. In the past twenty years, it has more than doubled itself: A debt of some 370 billion NIS has ballooned into some 750 billion NIS (not entirely linearly: Every few years, it goes down a bit). The significance of this fact is less serious than it sounds, as the more important question is not the size of the debt, but rather its size relative to the capital it is measured against. If the capital increases faster than the debt does, then the burden and the potential threat it presents are small. Based on this logic, it is customary to measure the national debt in percentages of GDP. This latter number of supposed to represent the “size of the economy,” and by comparing the debt to GDP, we can show the size of the debt burden compared to the state’s economic potential. In other words, the debt-to-GDP ratio represents the ability of the state to pay off its debts, and the degree of risk of default if a crisis arises which significantly shrinks its income or increases its spending. Responsible economic behavior, therefore, is one which aims to maintain a low debt-to-GDP ratio such that it will not be a danger.

Sufficiently high economic growth “erodes” the debt and makes it less significant relative to its size. When the economy grows significantly, the debt-to-GDP ratio can be brought down even with deficit spending. This is exactly what the State of Israel has done in the last twenty years. The debt doubled itself, but the GDP tripled itself, as a result, the debt-to-GDP ratio went down from 90% to 60%.

Either way, the state budget has been consistently out of balance: Spending outstrips income every year. When we hear reports of “surplus collection” from taxes, this does not mean tax revenue was more than government spending that year and that there is a surplus amount of money which can now be spread around. All “surplus collection” means is that the gap between government spending and revenue turned out to be smaller than forecasted by the Finance Ministry.

We all pay the price for the lack of budgetary responsibility of previous governments. In 2019, we will pay 39 billion NIS on the interest of debts we racked up. This means that if we did not have a national debt, we would have an additional 39 billion NIS a year for government spending or lowering taxes. For proportion’s sake: All of Israel’s income tax revenue for 2018 stood at 47 billion NIS. In other words, lacking a national debt, we could have almost entirely junked the income tax (!) and remained at the present level of government spending without cutting a thing. Alternatively, we could have injected government money into fields at the top of the public agenda. We could, for instance, peg the disability stipend to the minimum wage and still be left with 29 billion for any other purpose.

In other words, the interest burden is a needless millstone around the neck of the state budget, and without it, we could increase government spending and significantly reduce taxes. The interest rate itself is a derivative of the debt-to-GDP ratio, as the interest rate of bonds is a direct consequence of the assessment of the government’s ability to pay its debts over time – an assessment expressed in the reports of credit rating companies. In August 2018, for instance, in the wake of Israel’s reaching a debt-to-GDP ratio of “only” 60%, the S&P agency raised Israel’s rating from A+ to AA-. The higher the credit rating of a state, the lower the interest it needs to pay on its debts; a state which maintains a cautious budgetary policy will receive an increase in credit rating and thus also a cheaper debt. The smaller the debt-to-GDP ratio, the more exponentially interest decreases, as well as the opposite – which only increases the public interest in reducing the debt.

The accumulation of significant national debt in time of security quiet and economic prosperity endangers the state since the debt limits the national room to maneuver in time of economic crisis or worse – if war comes to our doorstep. In both these cases, government spending increases significantly while tax revenue decreases (naturally); but in these situations, we have no choice but to increase deficits that blow up the national debt. By the very nature of things, in these periods – when debt levels skyrocket – faith in the economy weakens and accordingly the rate of interest which lenders demand increases. It is therefore obvious that if the level of debt funding is already high, the funding of an enormous increase in the debt could become impossible and even lead to the state’s going entirely bankrupt – precisely what happened to the Israeli economy after 1973.

Until 1967, Israel maintained balanced budgets, some of which registered an actual surplus. But the more the years passed, the more Israel racked up increasingly serious deficits. People often speak of the trap of the post-Six-Day War euphoria which led to Israel’s military unreadiness in the Yom Kippur War. But this euphoria was not just expressed in security policy. Israel, which experienced a real wave of growth after the Six-Day War, entered into an economic euphoria which almost brought disaster to Israel’s economy when the Yom Kippur War broke out.

Here’s how Stanley Fischer and Michael Bruno, drafters of the economic stabilization plan (and later governors of the Bank of Israel) which saved Israel before it crashed into the abyss from the crisis, described it:

From a state of near-budgetary balance in the first part of the sixties (and as it was in the fifties, as well), the economy in the “golden age” between the Six Day War and the Yom Kippur War moved to a deficit equal to 12.6% of the GDP. In this period, there was an increase in civilian consumption, investments, and subsidies, and especially in military spending. In that period, the economy did not demand a significant increase in tax rates, because the rapid growth allowed for the taking of loans with great ease both at home and abroad … The government also succeeded in loaning significant sums from the Bank of Israel, thus printing money in an economy characterized by relative stability … Thus was the first seed planted which would cause problems … This was an era of expansion characterized by a psychological spirit of “We can do anything.” This was it possible to increase every sector of government spending and “wave all the flags” at once – the flags of security, development, and especially social welfare … The common approach in the relevant circles (which many economists, including the present authors, share) was that in such a flourishing economy … the time is right for a redivision of the national pie in favor of disadvantaged sectors in society.

The government consistently increased its spending, funding this via a growing debt, but it could not last forever. The War of Attrition which broke out at the end of the sixties added heavy expenses to the government, and a parallel slowdown in growth forced the government to remove some of the draconian taxes imposed on Israeli citizens until that period – leading to a decline in government revenue. The Yom Kippur War caught Israel in a state of high debt, and this debt spun out of control in the wake of that conflict.

Two efforts to cut government spending in the seventies – one under the Rabin government and another under Begin – failed for political reasons: The Israeli politicians who wished to be reelected did so by redistributing more and more money (we will return to discuss the incentives leading politicians to sabotage responsible economic behavior in depth). Alongside the raising of more debt, the government turned to a policy of printing money, but this revealed itself to be destructive, leading to hyperinflation which caused Israel to change its currency twice in a few years. We would not be amiss in claiming that in that period, the State of Israel was very close to becoming a failed state like Venezuela.

In the end, the Israeli economy was saved thanks to the economic stabilization plan which was led successfully by Prime Minister Shimon Peres in 1985. This plan included among other things a reduction in the budgets of government ministries, an increase in taxes, and a reduction in transfer payments and subsidies; in general, the stabilization plan led to a long process of a move from a largely planned economy to a market-based one. Israel ceased to fund its deficit via the printing of money, and from a peak of a 221% debt-to-GDP ratio in 1985, Israel dropped to “just” 100% four years later.

The trauma of the economic crisis of the eighties embedded the understanding that mechanisms should be created to prevent a similar scenario from recurring, one in which the national debt became an existential threat, from repeating itself. In 1992, towards the end of the Shamir government, the Law for Reducing the Deficit (known in the media as the “deficit target”) was passed for the first time, stating a measurable target which the government must not deviate from. Thanks to the law and the impressive growth of the nineties, the national debt shrank by 2000 to just 79% of GDP. However, in the wake of the Second Intifada and the bursting of the dot-com bubble, the national debt once again shot up, reaching 93% of GDP by 2003. The interest payments piling up threatened to cripple the government’s ability to function, and lacking another way out, then-Finance Minister Binyamin Netanyahu and then-Prime Minister Ariel Sharon led a policy of cutting government spending – a policy which reduced the debt once again. In 2004, the Finance Ministry led by Netanyahu, established a “spending rule” or numerator for the first time, a kind of updating of the deficit target which limited the increase in government spending by a fixed formula based on the size of the population. The Olmert government followed it and significantly reduced the debt-to-GDP ratio.

This trend did not last long. In 2011, swept up by the wave of the “social protest” and the Trajtenberg Committee formed in its wake, Netanyahu changed the rule he laid down and softened the limitation on public spending. He further softened it in 2013. In the years that have passed since, the deficit target gas been breached again and again as every government, with a simple majority in the Knesset, can change the Deficit Law and add all kinds of loopholes to spend public money as it sees fit. Anyone who looks at the law books will find something amusing (or perhaps depressing): Almost every year, since the 2013 budget, a specific amendment appears for that year alone. Beforehand, the government tried to justify the deviation from the deficit target on the grounds of one-time expenses (such as the Disengagement Plan, the Second Lebanon War, or the global economic crisis) but from the time of the social crisis, every additional annual budget has seen an “exception” added which allows for deviating from the deficit. When every budget becomes “exceptional,” the rule itself loses its meaning – as so long as there are 61 MKs in support of the budget, there are also 61 MKs voting in support of deviating from the deficit target, which makes it effectively irrelevant. The law meant to limit government spending has, therefore, become nothing more than a bureaucratic procedure on the path to excessive spending. And if so, to limit the government from deviating from deficit targets, a regular law is not enough. A stronger tool is needed.

The most recent Netanyahu governments brought down the debt-to-GDP ratio, but only moderately, and it stands today at just 60% of GDP – around the median rate of the OECD, significantly greater than Denmark (36%) and much smaller than the US (96%). Yet precisely in the last year, in which Israel’s credit rating was increased in the wake of a shrinking debt-to-GDP ratio, it is not clear whether this process of reducing the deficit is set to continue as the deficit target of the Finance Ministry, arrived at by the Israeli government as a whole and Finance Minister Kahlon in particular, has risen to a rate requiring an unrealistic rate of growth – 5% a year – in order for the debt to not balloon relative to the rest of the economy (and of course, there is no talking of reducing the debt to relieve the interest burden). Ignoring various accounting tricks meant to reduce the deficit for appearance’s sake (possible as the State Comptroller is investigating the matter as this article is being written), to preserve the debt at its present level as a percentage of GDP, we would need unprecedented growth of 6% per year, at a time when the current forecast of the Bank of Israel stands at just 3.4% while the OECD expects an even lower rate of 3.1%. This is the breaking of a 15-year trend, and the expectation is that the national debt will return to growth. We cannot but bemoan the fact that such things are happening under Netanyahu, whose stubborn economic policy succeeded in raising Israel’s credit rating to an all-time high.

Israeli history, therefore, teaches us two things. First, that funding public spending by turning to debt is the rule for fiscal policy in our parts and is not the exception; since the beginning, but especially since the sixties, the State of Israel has spent more than the tax it collects and therefore borrows money, with us paying the interest every year. Second, we learn that the strength of the mechanisms meant to prevent a dangerous increase in the national debt is in doubt; not only do governments change these mechanisms again and again – and always in a manner softening and neutering them – but the calls to utterly abolish them can be constantly heard from economists, politicians, and figures in the media. We will return to these insights in the coming chapters.

The Ideology of the National Debt

So far, we’ve briefly explained what national debt is, showing that the State of Israel has been a debt-based state for years. We also argued that Israel has no significant legal barrier limiting the government – any government – from breaching the deficit target as it sees fit. In this chapter, we will briefly take leave of the Israeli scene, to deal with it again at length in the main part of our article. As we said, a debt-based national economy is not a phenomenon unique to Israel but a common sight throughout the west – especially the US. To better understand how the existence of a growing national debt has become natural and taken for granted, and to properly understand the problem with this common phenomenon, we will turn to the thinking of American economist James Buchanan winner of the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1986 and the founder of public choice theory. In his writings, Buchanan deals at length with the phenomenon of the national debt and its economic and moral failings. We believe that awareness of Buchanan’s insights is necessary for the existence of any informed discussion regarding national debt in general and Israel’s in particular.

According to Buchanan, western fiscal history in general and that of America, in particular, can be divided into two succeeding periods which he terms the pre-Keynesian and post-Keynesian. Until the mid-twentieth century, the period in which the Keynesian revolution came to full fruition, fiscal conduct in the west, which served as the basis of American governmental policy over the generations, was based on two simple and complementary principles: (a) The government must not spend money without first imposing taxes; (b) The government must avoid funding public spending granting special benefits by creating a fiscal debt, as this imposes a financial burden on future generations, who will have to pay it back with interest.

These two principles expressed a general agreement that there was no fundamental difference between the fiscal behavior of a household and that of a national economy. Accordingly, thrift rather than largesse was considered a virtue in both the running of a household and the management of a national economy; just as the budget of a household needs to be balanced and not let spending outstrip income, so does the government budget need to be balanced and if possible enjoy a surplus. Along these lines, temporary deficits were considered legitimate only in exceptional circumstances such as wars, natural? disasters, or serious crises and were worthy of condemnation and dangerous in normal times not requiring exceptional spending. “Classical or pre-Keynesian fiscal principles,” Buchanan wrote, “supported a budgetary surplus in normal times which could serve as firm ground for more problematic times.”

As we said, the stance of the classical or pre-Keynesian fiscal approach towards the formation of a national debt was negative to its core. Funding based not on tax revenue but rather on the creation of debt was worthy of condemnation not just because it was proof of spendthrift behavior and irresponsibility on the part of politicians but also – and primarily – because funding through debt diverted the fiscal burden from those in the present and imposed it on the generations of the future. Debt-based funding allows people living in the present to enrich themselves at the expense of future generations. According to the classical fiscal approach, the choice between tax-based funding and debt-based funding is but a choice regarding when the bill comes due for public spending: Tax-based funding imposes the fiscal burden on the members of the political community living today, while debt-based funding is an obligation to pay for public spending in the future, with interest, delaying payment and imposing the fiscal burden on members of the future political community (or the same members of the community when the debt is paid off in the short term).

To this we should add another important insight which characterized classical fiscal thought and which will serve our purposes in the final part of the article: The argument that a citizen in a democratic state can make a balanced and rational assessment of the necessity and viability of various political choices regarding public spending if – and only if – these proposals are accompanied by a tax bill, with the cost being crystal clear to the taxpayer. The logic behind pegging the tax burden to the various proposals for public spending was clear: Such an institutional arrangement forces the citizen to take not only the advantages accompanying the public spending into account but also its tangible cost as a percentage of his disposable income.

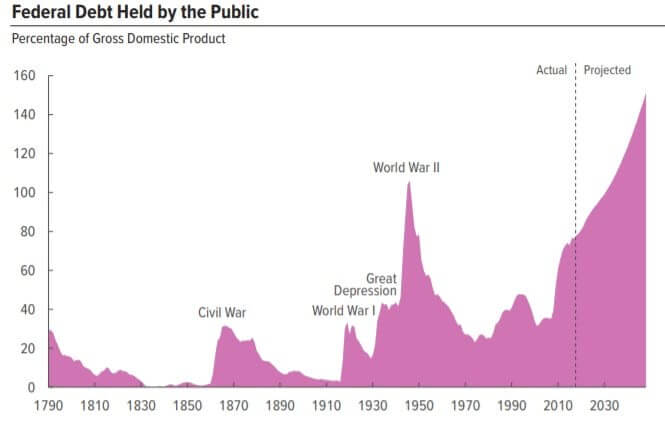

Various statistical data confirm the argument that governments in the past operated according to pre-Keynesian fiscal thinking. Here are the statistics on the American national debt for 1790-2015 as an example:

The pattern arising from the data is clear: Deficits were created primarily in time of war, while the budget had a generally favorable balance in peacetime, with the surplus serving to pay off war debts. Until 1946, the budgets showed a favorable balance and the national debt was the exception. And most of all: The general agreement was the debt-based funding in a time of need required a concomitant increase in the burden in the future as a means to close down the debt – whether via cutting public spending or by increasing the tax burden.

These characteristics, traits of the classical fiscal thinking we described above, were called “the fiscal constitution” by Buchanan. This was not a written constitution, of course, more like a set of beliefs, social conventions, and accepted norms which economists, but primarily politicians, saw as limiting their actions. The fiscal constitution effectively ensured careful use of public funds, and the analogy to the private household allowed the average citizen to easily judge the actions of his representatives. Public spending was not entirely rejected by the fiscal constitution, but it did require increasing the tax burden. This tight relationship not only created a negative political incentive to increase public spending but also ensured a minimal – and solely temporary – transfer of fiscal burdens to future generations. We now turn to the abrogation of the fiscal constitution in the mid-twentieth century and its consequences.

The book of famous British economist John Maynard Keynes The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, which was published in 1936, led to a global revolution in economic thinking – against the background of the Great Depression and at a time when support for the free market was at an all-time nadir. It is no wonder that Keynes’ book was received with a great deal of support and hardly any opposition. Yet still, the revolution he brought about – whose nature we will touch on shortly – was not immediate. Buchanan describes an ongoing historical process of close to 25 years in which Keynes ideas spread from a small group of economists to most people in the profession, followed by its adoption among journalists and public intellectuals, and ultimately by the politicians and the broader public. While fiscal theory began to change in the wake of Keynes during the thirties, actual fiscal policy began to change only a decade later with the complete trampling of the gates in the sixties.

Unlike the traditional fiscal approach which stressed the similarity between the financial running of a household and the financial management of a national economy, the Keynesian approach stressed the difference between the two. Responsibility and fiscal moderation expressed in avoiding entering into long-term debt, traits seen as correct to run a household, ceased to be seen as necessary for the running of a national economy. The reason for this lay, in Keynes’ view, in the difference between an internal debt incurred through the selling of bonds within the country and an external debt accumulated through the taking of loans from foreign governments and parties. According to Keynes, when the national debt is internal, both borrowers and lenders comprise the same national community, and therefore the profit and loss of these two groups cancel each other out; the future generations may bear the payment of interest, but those same generations benefit from the payment of interest on the debt. In practice, resources do not make their way from the national economy outward, to another economy, but are instead redistributed within that economy. Therefore, there is nothing wrong in the cumulative sense when it comes to interest payments on debt which we ostensibly owe “ourselves.” By contrast, external debt is less recommended according to Keynes, since it requires paying back interest on a debt to foreigners, making the national economy as a whole poorer in this sense.

The Keynesian approach opposed the argument that funding through debt imposes a burden on future taxpayers. Instead, and along the lines of classical economist David Ricardo’s arguments, the new fiscal approach argued that citizens living in a time when public spending is occurring are the ones who bear the economic burden – whether through public spending funded by the payment of taxes, or whether through debt-driven funding – as when the state borrows resources for some national project, people in the present are the ones forgoing alternative private uses such as the accumulation of capital, which they could have done with the money, and in this sense, they bear its true cost. Both taxpayers and bond buyers give up their money now in favor of increasing public spending which benefits everyone.

Finally, according to Keynes, economic prosperity – and not a balanced budget – is the goal of economic activity, and if one can only achieve the former with debt-driven funding, that’s the way to go. A deficit in the government budget is seen here as a small price to pay in exchange for growth and high rates of employment. The conclusion many drew from Keynes’ thinking – even if Keynes himself, who passed away in 1946, would not necessarily share it – was that balanced budgets are not important in themselves.

The totality of Keynesian arguments led to the rejection of the classical fiscal constitution which limited the economic activity of politicians over the years. These arguments led to nothing less than a paradigm shift in the science of economics. After Keynes, most economists ceased to look at the market in the same way their predecessors had; the common economic approach was seen now as outdated and passé.

The Keynesian economy developed in response to a situation of economic depression and very high unemployment rates, and debt-driven funding was seen as an appropriate response to this unique situation. But the years after WWII were of rapid economic growth and full employment, and this state of affairs not only did not justify funding public spending through debt, it required saving and paying off existing debts. But public spending, and with it the national debt, only increased in the US during the fifties; and this process reached its peak in the sixties under Kennedy, when taxes were significantly cut despite the existence of national debt and the lack of an economic downturn. As we showed, it was precisely in those years that the Israeli national debt began to grow significantly. “After 1964,” Buchanan summed up, “the United States went onto a track of fiscal irresponsibility unprecedented in the previous two hundred years of its existence … the Federal government budget rose, breaking new heights, and was funded largely if not entirely through deficit.” From a problematic but controlled practice, reserved for exceptional cases, debt-driven funding became the preferred default option.

What went wrong?

Not Right, and Especially Not Smart

As Buchanan notes, the intellectual legacy left behind by Keynes provided an intellectual rationalization for the natural tendency of politicians for deficit spending and increasing public spending through debt-driven funding. Keynes’ heritage (even though he would not necessarily agree with it) opened the door to unlimited political waste of public resources and the imposition of an increasing burden on future generations. It’s not for nothing that Buchanan called Keynesianism a “plague” which would in the long term turn out to be fatal for the functioning of a democratic regime.

The failure of the Keynesian model, Buchanan argued, lies in Keynes’ inability to notice the inseparable connection between economic theory and the political order in which it is embedded. As Buchanan noted, Keynes was no democrat; he was part of a dominant intellectual elite and believed that elites – not the masses – should lead the needed economic policy independently of political considerations. Keynes would be horrified, per Buchanan, if he saw how the democratic political system influenced economic policy. Keynes, and the many economists who see themselves as his successors, was blind to the system of incentives which face politicians in a democratic regime and the barriers which prevent them from adopting a correct economic policy, as these incentives do not exist in non-democratic regimes (or semi-democratic regimes led by elites of the likes of Keynes). Keynes made his suggestions before the theory of public choice was born, and his conclusions therefore entirely ignored the political context in which they were supposed to be implemented in practice.

The theory of public choice teaches us that an impartial examination of the democratic mechanism and the system of incentives operating within it leads us to the following upsetting conclusion: The relations between politicians and voting public increase the odds of reckless fiscal conduct based primarily on bloated national debts. The reason for this is obvious: Politicians want to be reelected, and therefore tend to increase public spending as proof of their work – without raising taxes on the public while doing so. In the same way, and as opposed to a private household, they have no incentive to end the fiscal year with a budget surplus which could serve their political opponents. On the contrary, they have all the incentives in the world to waste all the money they have at their disposal down to the last penny and even borrow additional money as a means for further public spending. Finally, and also contrary to private households, politicians have no incentive to take long periods of time into account – they need to appease as many pressure groups as possible here and now – and they tend to support a fiscal policy which secures their public support. In other words, it’s worthwhile for politicians not to be fiscally responsible. From their perspective, such irresponsibility is entirely rational. These trivial truths, absent from the Israeli public discourse, were noticed already by Adam Smith and David Hume.

Neither Hume, not Smith, not Buchanan – nor us – believe that politicians are bad people (though there are exceptions). But they are human beings like you and me, and like all human beings they are also driven by incentives – including the incentive of self-interest – and they tend to make decisions that benefit them even at the cost of deviating from the best economic logic. To sharpen the point, let’s quote Buchanan himself:

Elected representatives love to spend public money on projects producing certain visible pleasures for their voters. They do not like to impose taxes on those voters. The pre-Keynesian norm of balanced budgets served as a barrier to reckless spending … The destruction which Keynesianism brought on this norm, without providing a proper alternative, removed that barrier. Predictably, politicians responded by increasing spending far beyond income from taxes, by turning to deficits as a default option. They did not follow ostensibly Keynesian principles; they did not balance deficits created in times of recession with the accumulation of surplus in times of prosperity. The simple logic of Keynesian fiscal policy clearly failed when implemented in the democratic political framework.

The embedding of Keynes’ fiscal ideas in the democratic framework cannot but express itself in an ever-growing national debt and an ever-expanding public sector. Economic proposals that ignore the system of political incentives characteristic of democratic regimes are doomed to fail or lead to bad and unintended consequences.

The theory of public choice does not just deal with politicians in a democratic regime. It requires us to look at the citizenry itself. Most citizens in democratic societies are unaware of the burden imposed on them or their children when elected representatives decide to borrow money – often with their consent and encouragement. Unlike in their private life, and unlike when public spending is pegged to taxation, citizens cannot quantify the personal burden imposed on them as a percentage of the national fiscal burden. Voters can know abstractly that increasing the national debt imposes a burden on the community, but they do not (or cannot) know how to break it down into dollars and cents and understand how this burden harms them. While the price of goods and services in the private market is clear as day, when it comes to public services, the opposite is true. And this fact can explain the public tendency to approve every public service and view it positively. In other words, every citizen knows how much it costs to hire a tutor, but no citizen knows how much he is pitching into the funding of the budget of the Education Ministry, which provides “free” educational services to the public.

As far as the citizen is concerned, this lack of knowledge is quite rational: The time and resources needed from him to acquire this information are not worth the outcome as he has little influence as a single citizen. The result, so public choice theory tells us, is “rational ignorance” on the part of the taxpayer. In other words, the system of economic considerations is entirely distorted when it comes to public spending, as opposed to private spending, and all the more so when it comes to spending based on debt. This is a structural problem within the democratic mechanism that explains the public tendency to approve public spending if only because these costs are hidden, vague, and in the case of debt – also deferred. The democratic mechanism turning to debt-based funding creates nothing less than a fiscal illusion.

Let us sum up what we’ve stated thus far. Both politicians and the voting public have a serious problem of incentives: The former need to be elected by the eligible voters, many of whom want increased spending of the government in certain areas, but those same people are uninterested in paying heavy taxes. The political solution is entering into a deficit to earn the popularity of the voting public without paying a public price by raising taxes. This is why despite the spending rule in force in Israel since 2004, the deficit target has been breached again and again and governments cannot help themselves from spending money they do not have. This is a backwards system of incentives which we need to fight actively – through effective public pressure and properly anchored constitutional mechanisms. Without the establishment of legal barriers, public spending and with it the public sector and the public debt will continue to greatly expand.

We cannot, of course, rule out a scenario where political leaders suddenly discover the merits of fiscal discipline, economic responsibility, and a heroic stand in the face of social-populist pressures to increase public spending through debt-based funding; but any political system assuming the existence of such leaders – as a condition for optimal activity in the long term – is a problematic one. Our assumption needs to be entirely the opposite: We must assume that the democratic system puts irresponsible people in charge who go all the way in terms of heeding the democratic system of economic incentives, meaning politicians tending in favor of irresponsible economic behavior. We must expect the worst and not assume the optimistic scenario. A good political system is one which is adapted to human beings as they are – sometimes responsible, broad-minded, and with a complex worldview but quite often lacking responsibility, driven by narrow interests, and lacking any economic understanding. It is for this reason that we reject the idea that the appropriate solution to Israel’s unfortunate deficit problem lies in the election of responsible politicians. As we saw, debt-based funding is a systemic problem deriving from the fundamental system of incentives driving the democratic regime, not the wickedness of those involved or their corrupt character. Not only does this system serve the worst of politicians, but it also makes it hard for the best of them, as it punishes them for doing the right thing. Here’s how Buchanan summarized it:

An elected representative, who must be attentive to those who sent him, the bureaucratic system, and the voting public in general, needs some “supreme” law allowing him to stand fast against the unending pressures to increase public spending while maintaining low taxation.

Good politicians? Certainly. A legal framework that limits the conduct of irresponsible politicians and which helps the best of them act responsibly? More important. Much more.

Dispelling the Illusion

Thus, even if Keynes and his successors were right, a policy of debt-based funding, without a constitutional mechanism limiting it, leads to irresponsible financial behavior and inevitably endangers it, sooner or later. Ostensibly we could end the discussion here, but aside from the practical fallacy of Keynesian theory, it is simply incorrect. We do not need to refute it for our purposes, but we cannot avoid the issue entirely as it nevertheless serves as a consistent excuse for removing limitations on public spending. It is therefore proper that we turn now to the fallacies behind debt-driven funding – and the increasing of the national debt in general – again in the wake of Buchanan.

First, contrary to the Keynesian argument, there is no fundamental or supremely important difference between an internal national debt and an external national debt. This point, we should note, was refuted already by David Hume and Adam Smith: In the eyes of the former, this is nothing more than a rhetorical trick serving to hide a clear absurdity, while Smith dismissed the whole issue as nothing more than “sophistry.” Those who support a national debt claim that so long as the debt is internal, meaning so long as we “owe it to ourselves,” nothing bad can happen as the resources remain within the boundaries of the national economy. The right hand gives money to the left hand, but the body as a whole does not become weaker or poorer. By contrast, and this is the second part of the argument of supporters of debt-based funding – a debt of the second type, an external national debt, is to be condemned as it requires paying interest to foreigners and in this sense, the national economy as a whole becomes poorer.

Buchanan entirely refuted this approach with the following argument: in a situation in which an internal debt is created, the acquisition of the bonds to do so diverts resources from the private market to the public sector. In this sense, every internal loan or debt comes at the expense of private use of capital, as it reduces the total of usable private wealth, wealth which could have produced much social fruit if it remained in the private sector. By contrast, when the loan or debt is external, foreign money originating outside the national economy is funding the national public expenditure. True, in the future that economy will have to pay back the loan and its interest to outside parties (unlike an internal debt) but as opposed to the first scenario, the total amount of private capital in the economy is not harmed when creating the debt. In other words: When the loan is external, the total of private capital in society is larger than when the loan is internal. In the face of this insight, it is clear that the advantage of an internal debt over an external one is not at all obvious. According to Buchanan, so long as the interest rates are identical, the national community can be entirely indifferent to the type of debt it chooses.

Second, there is the very argument that there is no problem with an internal national debt, as we owe most of it to “ourselves” in any case, meaning the citizens who bought the bonds. But half a truth is worse than a lie; who are those people who compose this “ourselves”? We are not talking of the public at large and that there is no identity between the taxpaying public and the bond-purchasing public; these are specific citizens as those who buy bonds are the citizens who save up a lot and who invest their money (meaning economically well-off citizens). The richer the person, the larger his share of the national debt, in a disproportionate manner. While it’s true that bond-holders live in the same community as the taxpayers who do not own bonds, and in a sense, the economic advantage which bond-holders have is cancelled out by the tax burden of taxpayers, but why should we examine the community in such a collectivist manner?! Only if we look at the economy in an organic manner as a national economy – and not as an economy composed of different individuals with separate balances – can we speak of a “national cancelling out”; but if we look at events at the individual level, it is clear that the national debt harms many while enriching the few.

Famous Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises went further, arguing that the entire mechanism of debt is an expression of a destructive alliance between bond purchasers and the mechanism of the state, as the latter encourages the former to hand over their money in exchange for future financial security which does not exist in the free market. In other words: Through its mechanism of coercion, the state provides security for capitalists who prefer to buy bonds rather than risk their wealth in a competitive market. In this manner, Mises argued, the state and the capitalists profit off of the general public:

The state … places before the citizen an opportunity to invest his money in a safe manner and enjoy a stable income protected from any danger. It created an opening to free the individual from the need to take risks and earn his bread anew each day in the capitalist market. Those who invest in government bonds … escape the rules of the market and the authority of the consumers. They exempt themselves of the need to invest their resources such that they will best serve the needs and desires of the consumers. They have become insured, protected from the risks of a competitive market in which the cost of inefficiency is losses … His income ceases to be dependent on satisfying the needs of consumers maximally … He has ceased to be the servant of his fellow citizens … He has become the partner of the government in imposing authority on its subjects and taking their money … The entrepreneur, old and tired from the need to risk his capital … has preferred to invest in public bonds in order to free himself from the rules of the market.

The national debt, to put it clearly, is a regressive redistribution of money among the citizenry, in which taxpayers subsidize the big capitalists who can invest enormous sums into government bonds. Adam Smith already noted on this point that most of the public’s creditors are rich people.

Third, and in furtherance of the previous point, we need to properly understand who bears the burden of Keynesian debts and who profits from it – if at all. The claim that those who buy bonds equally bear the burden with taxpayers due to giving up on capital which could be used otherwise, is an absurd argument. People who buy bonds sacrifice nothing; all they are doing is giving up a particular sum of money with the expectation of receiving a larger amount in the future. This is an utterly ordinary act of trade in which both sides (the buyers of bonds and the state) profit. Otherwise, they would not have entered into the deal in the first place, something noted already by Adam Smith, as well. In other words, when a rich man buys government bonds, he is making an entirely rational choice in terms of his interest, as he is investing his money in solid bonds (meaning those with very little risk) and in return is receiving interest which increases his wealth.

The final and most important thing we need to clarify and refute is the claim that the loss of future taxpayers, who will have to pay the interest on the national debt, comes out of their profit, as they reap the fruits of the investments made possible by increasing public spending. This is the only claim in the Keynesian theory which does not contain flaws in terms of its logic. Still, it is the most mistaken of all of them. This is because it does not consider the conditions in which the theory is supposed to be implemented. First, this claim is only true given a reality in which an increase in spending is translated into investments which provide a yield and encourage growth, rather than the funding of benefits for the members of the community of the present in the form of various transfer payments and budgeting of services, and we have already seen that democratic systems encourage precisely the latter form of spending, providing immediate benefits to the voters and preferring them over the former.

But let’s assume that public spending is indeed channeled into investments. Even then, we need to remember that the significance of creating a debt means diverting resources from the private to the public sector. As such, the debt increases capital in society only in those cases where public investment bears fruit. Here, too, the incentive system does not work in the public’s favor. When it comes to private investment, the private capitalist and the entrepreneur bear the responsibility for their decisions. Investing private money in an unsuccessful channel means bankruptcy. Not so when it comes to the failed use of public money. In that case, the broader public bears the consequences of government mistakes. The fact that decision-makers do not bear direct responsibility makes it easier for them to take needless risks and invest in grandiose plans which a private entrepreneur risking his own money would not allow himself to take. Mises said it best in the following passage:

If the government uses its loans in favor of investments maximally benefiting consumers, and if it succeeds in these investments through free and equal competition with private entrepreneurs, then it is in a state similar to that of any businessman; it can meet interest payments as it has created a surplus. But if the government investment fails and a surplus is not created … The capital loaned shrinks or disappears entirely and there is no source from which it can pay the principal; then, taxation of the citizens is the only way to meet the payment schedule. In collecting taxes for these payments, the government is forcing the citizens to bear responsibility for the money wasted in the past.

But even in a case of successful public investment, which ostensibly justifies the debt, we see the fruits of this investment but we do not see the fruits which might have come in an alternative course of action: Private use of resources. After all, if the state had not borrowed money from those who bought government bonds, these last would have invested their money in the private market. In that case, both payments of taxes and interest on the debt would have been spared from the citizenry at large.

This is a classic case of “the seen and the unseen” in economic thinking. When money moves from private to public hands, we always see what the public hand is doing with it, but we can never know what the private hand would do with it if it still held onto it. So even in the case of a successful investment, it is not clear that the national economy and the public, in general, benefitted as opposed to a situation where an increase in spending did not occur.

In sum: When elected representatives operate rationally in light of the incentives in a democratic society, funding benefits for the community of the present via debt rather than investments in the future, the future taxpayers lose and pay the price. When they try to responsibly fund investments which fail – a likely possibility given the incentives encouraging them to take needless risks – the public loses again. When the investment pays off, the public does profit, but it’s not clear that it would not profit similarly or more so if the money raised from capitalists in the form of bonds served instead to fuel private investments in the free market. Thus, the entire doctrine of debts is aimed at a scenario which is unlikely to happen and which is difficult if not impossible to discern if it paid off. All this at a time when the most harmful scenarios will almost certainly occur, and at a high rate of frequency. Their harm is indeed easier to assess – but by that time, it’s too late to repair the damage.

Thus, the failure of the debt ideology is not merely theoretical but also – and primarily – a moral failing. When a government enters into a deficit, it is effectively imposing a tax on the future. Instead of collecting this tax today, from that public which chose to increase public spending, the state is effectively committing itself to impose taxes in the future to fund the spending, with interest. This future tax is imposed on those who are today young people, children, and even those not yet born.

The American colonists cried “no taxation without representation” and started a revolution for being taxed without being able to vote in the British Parliament across the sea. And here today the government, the representative of voters in our time, reimposes in every budget a tax on people who have no right to vote – the people of the future. Just as we pay today for the irresponsibility of those who served when we were children and before we were born, so are children today and people who have not yet born fated to pay for the deficit we are now entering.

For the Public Interest

The possibility of funding public spending by going into debt encourages public representatives to be light-headed when it comes to government commitments. The refuge of debt cultivates among public representatives traits contrary to what we expect of statesmen. Instead of moderation, restraint, and responsibility, the debt encourages them to act hastily and with abandon. The insight that society can live beyond its means is an open door calling for a thief. Elected representatives aware of being limited by fiscal legislation will tend, so we believe, to devote more attention to their choices, and act with greater efficiency with the limited resources at their disposal.

One often hears calls in the Israeli discourse to limit the majority for reasons of human and minority rights. We argue that one of the main, if not the primary justifications we can and should limit the conduct of a temporary majority is the freedom and welfare of the coming generations. Specifically, we argue that we should deny a temporary majority the option of imposing a financial burden on future generations and place them in danger. The proposed preventative measure is the passing of a new basic Law, Basic Law: The National Debt.

There is no moral or democratic justification for one generation consuming freely and leaving the next generation to pick up the check. There is also no economic logic. Debt-based public spending is the exploitation of the people of the future by the people of the present. This is not an act expressing the democratic ideal but rather its clear corruption. Society is not just a contract between people living today but as British statesman and Father of Conservatism Edmund Burke said: “between the living, dead, and those yet to be born.” No generation can be given the freedom to consume “for tomorrow we will die.”

It's important for us to stress in advance that the proposed law, whose main points we will address immediately, does not rule out public spending or socialist policy as such. We are not telling the government how much to waste and the law is silent when it comes to political decisions to increase public spending. We also recognize that in certain conditions, such as war or long-term public investment, there can be justification for turning to debt-based funding. The proposed law recognizes exceptional circumstances, but it is aimed first and foremost at the normal course of things. We argue that if politicians want to increase public spending, they may do so – but they must know this means increasing the tax burden. If the American Founding Fathers opposed taxation without representation, we oppose waste without taxation in a similar vein but recognize the legitimacy of waste backed by taxes. We do not hide the fact that we nevertheless believe that the citizens of Israel would be far more reserved about many public plans if the money needed for their implementation came directly from their pocket in the form of a tax.

We are aware of the enormous difficulty involved in the political realization of the present proposal or proposals along these lines. After all, when a society mired in great debt decides to pay it back, it is explicitly choosing to prefer the future at the expense of the present and in this sense is cutting back on its present pleasures. Once a particular public enters into a big debt, it becomes very hard for it to get out of it as the democratic mechanism itself serves as an obstacle.

Beyond this, the passing of a Basic Law is always a controversial thing in Israel, and when it comes to a Basic Law with economic consequences, it is expected that those profiting from the present order will rebel against it. The Histadrut and public sector workers will likely be the biggest opponents of a zero-deficit policy, judging by the enormous number of articles in the Histadrut paper Davar Rishon praising the increase in the national debt. The Histadrut benefits from budgetary irresponsibility in several ways. First, when government spending increases, regardless of the purpose, more workers are hired and existing ones are paid more, and so do those workers unionized by the Histadrut and the Histadrut as a body (collecting dues based on salary) directly profit. Therefore, any law and rule which limits government spending will directly harm them. Second, Histadrut members earn far above the average and much more than normal private-sector wages, and can therefore save much more. They invest this money among other things in bonds issued by the State of Israel, the interest on which they directly collect. In addition, Histadrut workers, primarily in the public sector, are commonly given extensive pension benefits. Therefore, public sector workers are a large portion of the State of Israel’s creditors, and they directly profit from our debt. The strong workers in every union, and public-sector unions in particular, are usually the older, veteran workers. Therefore, it’s easy to see why the Histadrut will support imposing taxes on the next generation to significantly increase government spending.

An important party which may also oppose the effort are the pension funds benefiting from designated bonds with a particularly high yield which the state issues to subsidize them. Also, other financial bodies that rely on Israeli government bonds as a tool for managing finances will be opposed, as they directly profit from the interest on debts which the state incurs. The sale of fewer bonds and the end of their excess subsidy will attract many to invest in other channels or independently. Pension funds have enormous power in the Israeli economy, and they may use it to pressure politicians and public opinion against closing down the deficit and reducing the national debt.

Ideological socialists and economic ignoramuses will also oppose the passing of an economic Basic Law. The Scandinavian countries, which are often brought as an example of socialism which “works,” tend to maintain iron discipline when it comes to budgets, with zero and even negative deficits (budget surpluses!), enjoying a drastically lower debt-to-GDP ratio than we do. Yet this important fact is something Israeli socialists tend to ignore. Avi Gabai, for instance, published his economic program a year ago, which included an enormous increase in the national debt to build hundreds of thousands of public housing apartments and greatly increasing government spending on welfare and defense. In the eyes of many socialists, there is a need to increase public spending at all costs (literally). Since raising taxes is not popular in the Israeli public, the easiest way to advertise grandiose plans for increasing public spending goes through, as we noted a few times, going deep into debt. The national debt is a complex and unintuitive subject, and it therefore has many supporters among the public – as though one can invent resources that do not exist and use them to fund projects. An effective basic law will take this significant propagandistic tool away from the socialists, requiring them to admit that their expensive plans necessarily require imposing a heavy tax burden on the entire populace.

A similar law to what we are proposing is already in force in Germany today. In 2011, in the face of the high national debt which Germany entered in the wake of the global economic crisis of 2008, a “debt brake” was added to the German constitution. This addition to the constitution, which went into full force in 2016, saw Germany move for the first time in decades from a budget deficit to a budget surplus, and Germany’s “debt clock” began to tick backwards. Germany’s debt brake states that the government cannot spend more than it takes in aside from a natural disaster or an “emergency case outside of the government’s control,” such as an international economic crisis or a large-scale war.

The German law was passed due to the need to drastically and immediately reduce the national debt (Germany’s debt-to-GDP ratio presently stands at around 80%). We, by contrast, are aiming for a more moderate and long-term solution. Therefore, the Basic Law we are proposing is much less extreme. It allows governments to enter into debts in routine times as well- but only for the purpose of long-term infrastructure projects which future generations will also necessarily enjoy. However, we are uninterested in creating a situation where every government expense is broadly defined as an “investment” and therefore entirely based on debt. Since we are realistic about politician’s behavior, we fear that such a situation could lead to an even bigger deficit than that which exists today. Therefore, like the lender demanding that the business owner invest some of his own money as “seriousness pay” and share the risk that the investment doesn’t go as planned, we also demand that the government (in section 3) invest similar “seriousness pay” with a sum identical to that which it intends to loan from the public.

In addition, entering into debt as a result of a unique situation like a natural disaster or war will require the government to declare the date in which the entire debt will be repaid for this exceptional situation, and it will not be allowed to kick the debt can down the road. This, in order to prevent a situation in which a debt that began in the wake of an emergency situation continues into routine life. With the aid of these checks and balances, we hope to create an infrastructure for responsible budgetary management which will increase trust in government, and thus strengthen us economically and internationally, while protecting the rights of the next generation from being abused by the populists of the present one.

Basic Law: The National Debt

1. The planned expenses of government will be pegged to the forecasted collection of taxes that year. In a state of affairs which is not an emergency situation, no public expense will be allowed which deviates from the same.

2. Deficit-based funding will nevertheless be allowed, by a decision of a special majority of the Knesset, only in cases of irregular circumstances including war, environmental disaster, global economic crisis, or long-term social investment.

3. If the legislator shall decide to find a project of long-term social investment by entering into debt, the State of Israel will for every project spend a shekel of taxpayer money for every shekel taken as a loan, and sell bonds specifically for this project.

Sagi Barmak is a research fellow at the Tikvah Fund. Idan Eretz is a liberal activist and one of the founders of Hofesh Kekulanu [Freedom For All of Us]

![המחאה החברתית קיץ 2011, תמונה מהפגנה בבאר שבע. תמונה ראשית: באדיבות ויקישיתוף. Eman [CC0]](https://hashiloach.org.il/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/wsi-imageoptim-beer_sheva_2011_housing_protests782_eman-cc0-1880x600.jpg)